American Prayer

mixed media (oil and acrylic on canvas), 2000, 213 x 187 cm / 83 x 73''

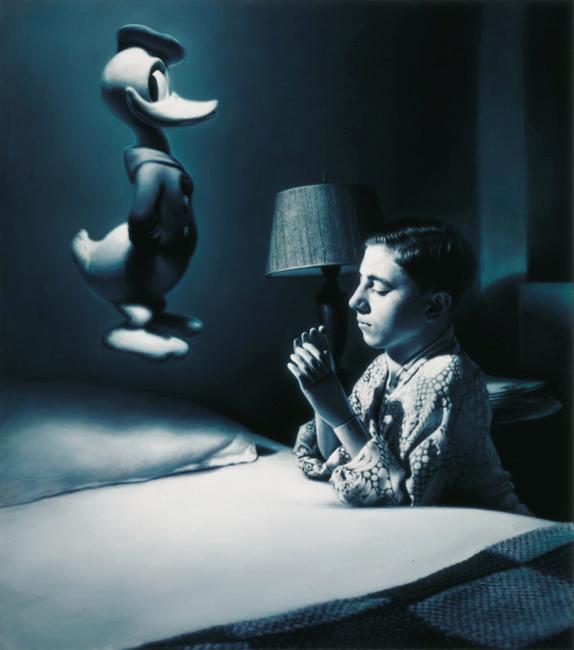

Ever since I clicked on it, Gottfried Helnwein’s "American Prayer" (2000) has taken up residency in my mind. The image shows a boy kneeling beside his bed, praying to a floating apparition of Donald Duck. On closer examination, it appears that the boy is not quite real: marionette joints are showing at the wrists and, compared to the face, the hands look wooden. Could it be Pinocchio, and would he be praying not to become a real boy but an indestructible cartoon character?

At first I thought it was just a memorable cartoon, worthy of a printout and a magnet on the fridge. Then it dawned on me that "American Prayer" mimics a digitally altered photograph while concealing its "true” existence as a painting. Reproduced on the computer screen, "American Prayer" shows no brush marks, but the caption gives the secret away: oil and acrylic on canvas, 213 cm x 187 cm. This large-scale, meticulously rendered painting seems at odds with its subject matter: a marionette praying to a duck. At minimum, the use of paint here is an indication that more is at stake than simple amusement.

I began to discover a semiotic richness in this painting worthy of what W.J.T. Mitchell has called a "metapicture" - a "picture that [is] used to show what a picture is". Mitchell situates the concept of metapicture in "'iconology', the study of the general field of images and their relation to discourse," thereby cutting across Greenbergian self-reflexivity into an expanded context that includes popular culture as well as contemporary art. In this wider cultural field, a metapicture does more than reflect on the nature of the picture itself and calls into question "the self-understanding of the observer". I will argue that "American Prayer" derives its theoretical relevance partly from its concealed hybridity, from the interplay between technological media and painting. In this work, the substitution of one medium by another reinforces the meaning that can be created from the iconographic substitution of the child by Pinocchio, and the replacement of the deity by Donald. In the end, Donald’s sideways glance at us indicates that this picture is really about us, the observers; it questions our own place in a cultural web of illusionism spun from the abiding human desire to overcome death.

Somewhere, in a private collection, an auratic, singular painting exists that is titled "American Prayer". On the screen, the painting reverts to its photographic and digital sources and attains eternal life in digital reproduction. The painting itself has a limited life span that will depend on curatorial care and the absence of disasters that could destroy it. Its reproduction, however, is an immaterial, pixelated entity that will never show a trace of decay. Its demise is kept at bay for as long as the hardware and the sofware are available to support it. "Let me be an image and never die", the boy might well be praying.

Once upon a time Pinocchio wanted to become wholly human. In this picture, he appears to have been partially successful; with the exception of his hands and arms, the boy does not look like a wooden doll at all. The nose, which in the original story grew with every lie, appears to have settled into an acceptable size. No more lies. But now, half-real and half-mechanical, why would Pinocchio pray for puny human limbs that would be less durable than his wooden ones? Why would he pray for a heart that, at some future moment, will stop and signal his death? Why should he wish for flesh that, like the original painting, will rot away eventually? With cartoons on his mind, it seems more likely that he is praying for a post-human condition. To become human means to die, but the airborne duck holds a promise of transcendence of death.

"American Prayer" presents three possibilities for Pinocchio’s existential identity: he could become a human boy, or he could remain the cyborg-like, "transhuman" creature he appears to be at present. Or, the third possibility: fervent prayer may bring him the eternal life of a cartoon image. Pinocchio’s choices form a parody that reflects the serious search for identity in a time when unprecedented progress in medical science, biotechnology, and virtual reality have shaken our beliefs of what it means to be human. The increasing reliance and dependence on technology in our everyday lives changes our sense of identity in ways that seem incomparable to anything we have experienced before. It is easy to forget that self reflection has a culture-specific history, in which imagery has played, and continues to play, an important role.

Our particular Western legacy of identity formation is entangled with a predilection for pictures that resemble reality. The art of illusion has deep roots in Western art dating back to the Classical Greek period. Of course, since the nineteenth century, many, if not most, artists and art historians have worked against the mimetic tradition. The mirror has been broken; Ernst Gombrich considered Ruskin’s Modern Painters of 1843 the last art historical treatise to provide a story of art as one of continuing progress towards an ever-more-perfect illusion of reality. Since then, valuations of technical skill and artistic inventions that help to represent an illusion of reality have not ranked high in art-historical discourse.

If we step outside this narrow discourse, however, we find that a drive towards the perfection of illusion in representation has been alive and well from the painted panoramas of the nineteenth century to the IMAX theatres and computer games of the twenty-first. Contemporary new-media art, with its use of the technologies of virtual reality and immersion, brings into a renewed focus the desire to recognize reality in visual representation that has played such a considerable part in Western art history.

Art historian Oliver Grau, in his book on virtual art and its historical precedents, sees the immersive space of virtual reality as a culmination of the drive to enter into the image and collapse the distance between reality and illusion. He writes: "There are only old and new media, old and new attempts to create illusions: It is imperative that we engage critically with their history and their future development." I will argue that "American Prayer" constitutes such a critical engagement with both old and new media and provides the site for an analysis of the different contributions that photography, digital manipulation, and painting bring to the illusionism of an image.

Since the Enlightenment, when the interest in the subjective experience of reality emerged, the philosophical question of what constitutes the real has been an important one for artists and art historians. The photograph’s indexical claim to the real sharpened this discourse, which continues to have a strong relevance in present-day explorations of representation. In this essay, however, I will have to sidestep the issue of photography and the real that figures so prominently in the photo-based painting of artists such as Gerhard Richter and Taras Polataiko. As I will argue, "American Prayer" signals a different issue. Helnwein’s hybrid work comments on the aesthetic realities we imagine, the special effects that create other worlds and other lives so realistically that we willingly suspend our disbelief. It examines the desire for an escape from embodied existence into imagery that looks as believable as the real world and promises to be far superior in its wish-fulfillment.

Helnwein has sensed the superiority of cartoon life over real life ever since he was a child. A biographical story, which begins to take on a mythical character through slightly different repetitions on his various websites, explains his obsession with Disney characters. Growing up in dreary, destructed post-war Vienna, the young boy was surrounded by unsmiling people haunted by a recent past they could never speak about. What changed his life was the first German-language Disney comic book that his father brought home one day. Opening the book felt like finally arriving in a world where he belonged: "a decent world where one could get flattened by steam-rollers and perforated by bullets without serious harm. A world in which the people still looked proper, with yellow beaks or black knobs instead of noses."

Half a century later, Helnwein’s childhood identification with immortal cartoon characters finds an uncanny resonance in the grown-up technological fantasies of cybernetics, cryogenics, and virtual reality. The half-human Pinocchio of "American Prayer" is a little bionic man; his mechanical limbs make him as "transhuman" as the "exoskeleton" that augments the knuckles and bones of the techno-performance artist Stelarc.

The unsquashable duck in the painting may be seen to spoof technophiles’ desire to overcome the deficiencies of the human body through technology (Donald Duck as the post human ideal), but the joke includes Helnwein himself. He leaves enough biographical clues in the painting to indicate that he is not immune to the lure of a promise of immortality, even if he left such dreams behind in childhood. The stark, old-fashioned bedroom with its hand-knitted bedspread and smooth white bed sheets (which reflect the "heavenly" light so well) harks back to the artist’s childhood. The reference is corroborated by the boy’s old fashioned hairstyle, while the oddly patterned bathrobe, worn over pyjamas, also speaks of a less casual and less commercial time. Surely, a boy so enamoured with Donald Duck would be wearing Disney PJs in this day and age! Also missing in this dated children’s room are the Disney sheets, Disney lamp, Disney action figures, Disney film posters, and Disney wastebasket.

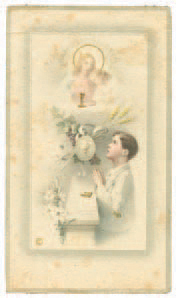

Another biographical trace can be found in the picture’s simulation of a religious picture genre that was integral to the Catholic tradition that Helnwein grew up in. In his image-starved childhood, the comic book formed a radiant exception to the religious imagery of church and school. He became familiar with pious paintings in the form of prints he was given as awards for good behaviour.

9.2 Anon., Prayer Picture

1950

The painting shows an ironic affinity with Andy Warhol’s "Myths" series of 1981 as well. Warhol’s fear of dying and his quest to find eternal life in the flood of consumer products and images resonate critically, if sympathetically, in "American Prayer". New York-based critic and curator Christopher Phillips has connected Warhol’s death and disaster series with his notions of serial reproduction, consumer commodity culture, and celebrity. Phillips extracts salient points from Günther Anders’s 1956 book, "Die Antiquiertheit des Menschen" [The Antiquatedness of Humankind], to shed light on Warhol’s insights into the changing concepts of human identity in an age of mass-produced goods and images. Writing afer the Second World War, in an era of accelerated consumerism, Anders, a German Jewish essayist, could no longer share Walter Benjamin’s optimism about the cultural and political potential of mechanical reproduction. Rather, he recognized that this potential would be completely assimilated in the profit-oriented mass production of a consumer society.

A pessimist like Jean Baudrillard and Guy Debord, Anders saw the flood of camera-generated images, with their heightened sense of realism, blur the distinction between real events and their representations. He argued that under the gaze of photo, film, and television, real life is degraded, as is the body. Phillips writes: "In a world driven by the tempo of mass production and consumption, that which cannot be conceived, produced and disseminated in multiple form can no longer have significant existence".

Myths (The Shadow)

Screenprint, 1981

Phillips argues that, "for Anders, mass-media celebrities play a special role as prototypes of a new kind of humanity: pioneers who have consciously reduced themselves to a set of easily transmissible features and thus stepped out onto the 'ontologically higher' plane of serial production". According to Phillips, "Myths", which includes screenprints of idols such as Greta Garbo, Superman, Howdy Doody, Dracula, and Mickey Mouse, constitutes Warhol’s particular effort to reach such an "ontologically higher plane". In and among the stars, Warhol inserts a self-portrait, "The Shadow". "The aura of glamour that surrounds Warhol’s celebrity icons springs directly from the sense that the subjects have crossed over to the same zone of timeless ubiquity occupied by consumer products like Campbell’s soup", Phillips explains. "Warhol set out to achieve the same kind of transcendence, the only one in which he could fully believe".

In contrast to Warhol’s submersion into consumer culture - ironically or not - "American Prayer" is representative of Helnwein’s moral defiance. While Warhol appears (or pretends) to relish the interchangeability of commodities, images, and human beings, Helnwein loads his images with enough deconstructive power to implode their illusions from within. Like the abstract Modernists and the 1970s conceptualists who attempted to break the stronghold of illusionism in Western visual art and culture, Helnwein works against the illusion of reality presented on the picture plane. But, unlike them, he does not negate illusionistic representation.

Far from being an iconoclast, he uses his extraordinary skills in all artistic media, particularly in painting, to show that an image is just an image. Because he intermingles unadulterated photographs with photo-based paintings as well as with pure paintings, the first thing the viewer wants to do when confronted with his work is to find out how it was done. By eliciting this curiosity about the construction of the image, Helnwein foregrounds the artifice of the image. Appealing as strongly to illusion as popular culture does, Helnwein confronts the consumer culture on its very own grounds. He uses a popular lexicon and popular media, as well as mass reproduction and dissemination techniques (his websites are exceptionally accessible and comprehensive).

Helnwein’s work in general, and "American Prayer" in particular, demonstrate the pertinent difference between illusion and illusionism that Mitchell has established. "Illusionism," Mitchell writes, "is something built into the very conditions of sentience and extends from areas of animal behaviour such as camouflage and mimicry right into trompe-l’oeil". Like the legendary bird pecking at Zeuxis’ painted grapes, human beings too can be fooled by copies. Camouflage in the animal kingdom, however, lacks intention: the fish may be tricked by the fly that hooks it, but he will never create a fly. Cultural illusionisms, in contrast, are intentional and therefore fall into a different category. In contrast to illusion "as error, delusion, or false belief", Mitchell sees illusionism as "playing with illusions, the self-conscious exploitation of illusion as a cultural practice for social ends". Whatever these social ends - religious, political, or commercial - illusionism in Western art and popular culture has underpinned and furthered them. For this reason, illusionism requires a critical and historical analysis across the fields of art, popular culture, and technological inventions in representation. "American Prayer" provokes such an analysis of the most groundbreaking invention in illusionistic representation: the photograph.

Although our habit of trust in the veracity of the photo has been seriously eroded since the invention of digital transformation of images, a lingering sense of reality remains associated with anything that is captured by the camera's eye, even if it is a digital eye. The photographer's intent, whether to record reality straight-forwardly or to alter reality through unusual camera settings or manipulation of the negative in the darkroom, does not change the sense of indexical truth that clings to any photograph. Helnwein’s realistic painting style in "American Prayer" creates the look of a photograph to exploit our habitual expectation of truth in photography; the photographic realism of the incongruent scene is what makes the irony work. We weren’t expecting a duck, and certainly not the cartoon kind, in this pious picture. But here he is, in all his glory, captured by the camera.

Petra Halkes

McGill-Queen's University Press

IMAGE & IMAGINATION, Le Mois de la Photo à Montréal 2005

GOTTFRIED HELNWEIN’S AMERICAN PRAYER, A Fable in Pixels and Paint - PART 2